By Oula Mahfouz and Michael Seifert

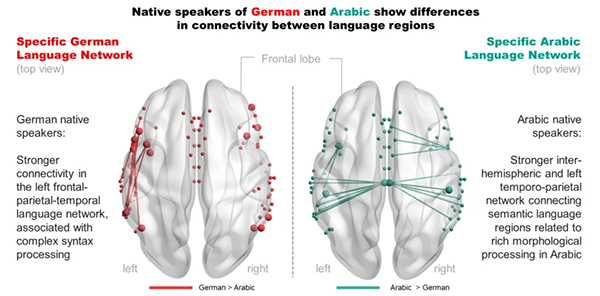

Brain researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, have used a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner to compare how language processing works in the brains of Arabic and German native speakers. In the process, they came across quite surprising results: “Arabic speakers have a strong connection between the two hemispheres of the brain, whereas in German native speakers the connections within the left brain hemisphere are more strongly developed,” explains Alfred Anwander, the head of the study in an interview with tünews INTERNATIONAL. “Our study is one of the first in which such differences have been demonstrated. There is actually a widespread view among linguists that all brains process language in the same way, that there is a universal network for language processing that works in roughly the same way for all languages, even if the languages differ greatly.”

Much has been written in the Arab world about these new research findings, published in April, Oula Mahfouz noted. “People have taken the study there in the social media in an evaluative way according to the motto: Our language is great, it is much better than the German language, because it uses both halves of the brain,” she reports to Alfred Anwander. Anwander immediately counters this clearly: “Languages have different methods of explaining the world, and the brain adapts to them. There is no hierarchy among languages, only the fact that apparently brain connections differ between languages.” And he compares this to the differences between tall and short people: “Tall people can reach up high on a shelf, but they don’t have the legroom that short people have on an airplane or in a movie theater.”

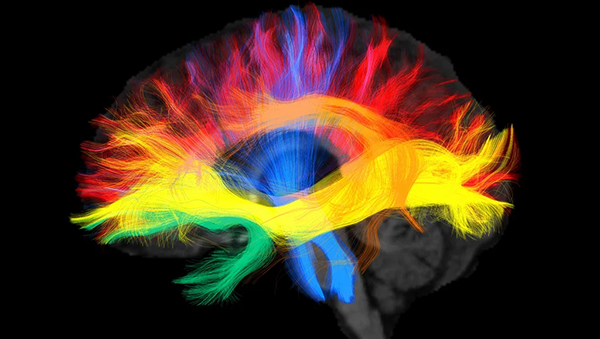

But how has it been possible to determine these differences? Anwander explains, “In MRI, people are pushed into a tube where strong magnetic fields are used to measure and visualize human anatomy. Our examination of the brain focuses specifically on the connections between the nerve fibers. Their course can be made visible in the MRI—just as you can see the direction of wood fibers on a tabletop. We already know from earlier studies of language research in which areas of the brain the various parts of language processing take place, e.g. the motor function of speech, language comprehension, but also the complex processing of sentence structure and word meaning. We were now interested in calculating the course of the nerve fiber tracts between the speech processing centers. The strength of this network of nerve fiber connections can then be statistically compared between the two native language groups.”

So how do scientists explain the differences in nerve fiber connections between the two languages? Alfred Anwander explains: “In German, the word order in a sentence is very flexible: a verb can be at the beginning, in the middle or at the end. You have to listen to the sentence all the way to the end to know what is subject and what is object. The center for processing sentence structure is in the left hemisphere of the brain, so the connections there are more pronounced in German speakers. Arabic may be simpler in this respect. But there the complexity lies in a different area, for example in the richness of the vocabulary and thus in the word meaning, but also in the marking of the grammatical function of the words. This makes it more difficult to understand the individual words, and the network for this is then more developed in the brain.”

The neuroscientist also finds these differences very exciting because they could perhaps be made fruitful for foreign language teaching. A second study is investigating what happens in the brains of Arabic speakers while they are learning German. The aim is to find out how the neural network changes when learning a new language. The findings could ultimately be used to improve methods for learning foreign languages.

Anwander can also already reveal the first results from a preliminary publication. “In fact, we found that learning a foreign language causes changes in the brain. We studied a large group of Arabic-speaking adults who studied German intensively for six months. The language network in both hemispheres of the brain strengthened significantly as a result of intensive vocabulary learning. At the same time, the strong connections between the two hemispheres of the brain, which are actually typical for Arabic speakers, decreased. In summary, our studies provide new insights into how the brain adapts to cognitive demands—our structural network of language is shaped by our native language, but changes when we learn a foreign language.”

tun23052301

www.tuenews.de

MRT-Darstellung des Sprachnetzwerks im Gehirn. Foto: Max-Planck-Institut für Kognitions- und Neurowissenschaften (MPI CBS) in Leipzig

002006

002007