By Michael Seifert

“A house that someone covered with a sheet like a treasure chest. … One entered closed-eyed, one came out open-eyed. The solution to the riddle: the school.” A famous Babylonian riddle, almost 4000 years old, shows that schools already existed at that time in Mesopotamia, the Mesopotamia of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in what is now Iraq. These were the oldest schools about which anything is known through written tradition. Among others, Konrad Volk, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Oriental Philology at the University of Tübingen, who was interviewed by tünews INTERNATIONAL, is researching these schools.

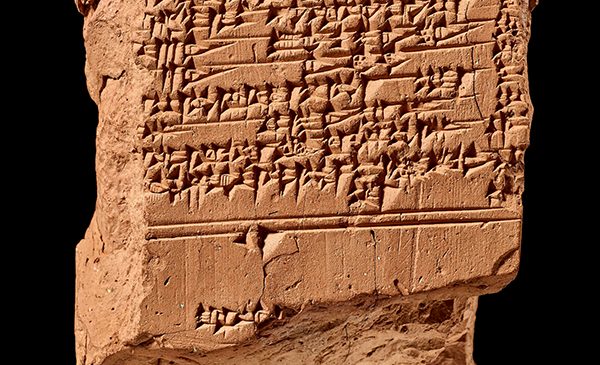

Writing with cuneiform script in the Sumerian language, which was already extinct at that time, was taught at these Babylonian schools. “This dead language was the language of the cultural tradition in which the Babylonians saw themselves until the turn of time around the birth of Christ.” He said this could be compared to the function of Latin for the Catholic Church throughout the Middle Ages and into modern times. The “dead” language of scholars, Latin, has also been taught, spoken and written at European universities since the Middle Ages. And this Latin is still taught today as a “foreign language” at German grammar schools.

We know how things were at the Babylonian schools from texts from 3800 years ago. Konrad Volk refers to the “satirical dialogue” about the experiences of a pupil. Much of it seems familiar from today, right up to the “snack” that the mother gives the pupil to take to school. There is also talk of homework, of mathematics lessons with “solutions to arithmetic tables with calculation and balancing tasks”. The pupil is reprimanded by the teacher: “Your handwriting is miserable!” Strict are also the rules of conduct the pupil talks about: “I must not be late” or “on no matter did I raise my voice unasked”. One is also not allowed to get up or go out without permission. It is also forbidden to speak in one’s mother tongue, Babylonian, instead of the dead Sumerian language. The student also names sanctions against violations: “Then he (the teacher) hit me …” For the pupil, this leads to rejection of the school: “I began to hate the art of writing.” A solution to the problem may be to bribe the teacher by inviting him to a big dinner given by his parents: “Premium beer was poured for him there.” The result: “The master thus gave him a favourable report card.”

Konrad Volk cites the training as a scribe as the background to the founding of “schools”: “This was an extremely important and respected profession. The driving force behind the development of writing was the population growth in cities, whose supply had to be ensured by a tightly organised administration. For the city of Uruk alone, it is assumed that at least 20,000 people settled on 400 hectares of walled area in the period from about 3100 to 2900. Everything was documented, from economic contracts to pay slips and finally literary texts. There were thousands of scribes for this. At times, scribes were also recruited from abroad.” Teaching materials have survived, for example, in the form of bilingual Sumerian-Alt Babylonian dictionaries. “Linguistics and grammar were also already developing at this time. The dissection and atomisation of language into its smallest parts took place, as in modern linguistics, in order to better teach language and writing.” Volk is certain that schools also existed in Sumerian times, i.e. in the late fourth millennium BC, as word lists already exist from that time.

Another “dialogue between school supervisor and school graduate” in Sumerian deals with “the maxims of action of the school that are valid at all times”, according to Volk. According to this, the pupil is “like a swaying reed” and is “put to work”, guided and educated by the teacher. The pupil sums up his schooling: “Like a puppy (a dog cub blind at birth) I was, long since I opened my eyes and therefore acted as a human being.”

There are also statements about pedagogy: at first, everything is just copied down, which the teacher presents perfectly: “Through his hint, even an idiot can become understanding. On the clay he guided my hand, the right way he made me take. My mouth he opened for suitable words, wise counsel he found for me. … Ever since I was little, you have tested me, closely observed my way of life, purified it like beautiful silver.” In conclusion, the teacher pays respect to his now former pupil: “The masters who know everything should hold one like you in high esteem! Boy, who sat listening to my words, you have gladdened my heart. …Let it be known that you are a man of understanding.”

Volk explains that the school was far more than just a writer’s education: “It was about holistic education. The children studied literary works and history. The famous Gilgamesh epic was also important for the educational horizon. Ultimately, it was about opening their eyes to life and the surrounding world.”

In one respect, the Babylonian school system was clearly more progressive than the first European schools: “Although the scribal profession was male-dominated, girls were certainly trained as scribes.”

The texts quoted from were taken from the text collection “Erzählungen aus dem Land Sumer” (Tales from the Land of Sumer) edited by Konrad Volk (Wiesbaden 2015). In it, literary texts with explanations are also found on creation myths, the birth and growth of man, the ruling dynasties, war and peace, and life and death.

tun22090606

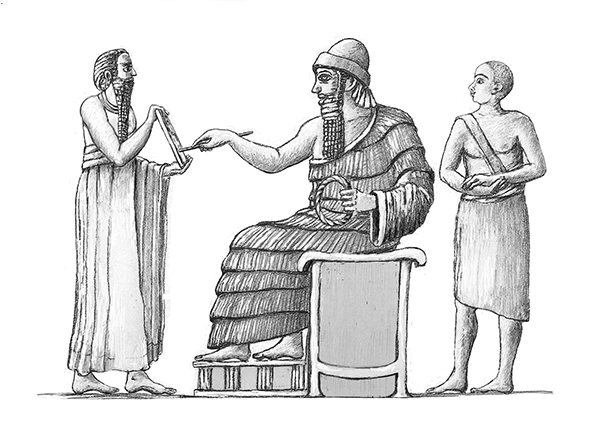

Künstlerische Illustration zum Schulalltag in Babylonien von Karl-Heinz Bohny. Foto: © Karl-Heinz Bohny.

001720

001721